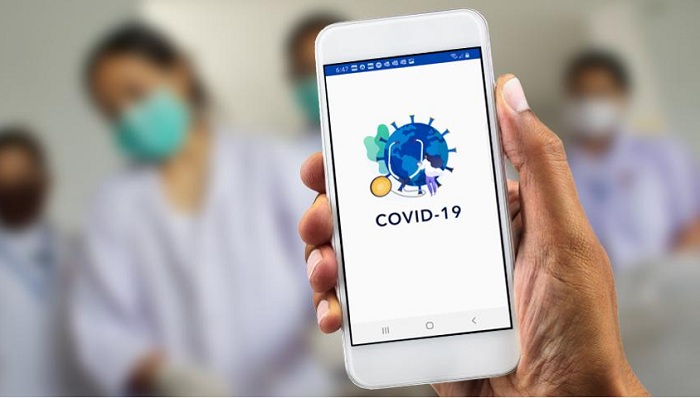

Engineers at Worcester Polytechnic Institute and Virginia Tech are collaborating on a smartphone app that can help conduct contact tracing needed to contain the spread of COVID-19 without risking users’ privacy or personal security. Their work is funded by a one-year, $120,000 RAPID grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Investigating the close contacts of people who have tested positive for a virus-like COVID-19 is a critical part of the strategy to mitigate the virus’s spread. Contact tracing investigations have found that most people have between two and 10 close contacts, creating a quickly spreading network of potential infections that can exacerbate and prolong a pandemic.

The aim of contract tracing is to find close contacts quickly so they can be tested and asked to quarantine, limiting the number of people they, in turn, could infect.

Typically, contract tracing is a manual process, with public health workers interviewing an infected person’s close contacts. “We can make that process easier, faster, and more efficient if we supplement this manual contact tracing by digitally obtaining accurate and pinpointed contact information,” said Patrick Schaumont, professor of electrical and computer engineering at WPI and a co-principal investigator on the project.

However, some have bristled over the use of digital technology–especially using smartphones, for contract tracing–concerned that the technology could reveal personal information, including the movements of people being traced and who those people have contact with.

Schaumont, who has a background in security and privacy research, said it’s possible to use smartphones as contract tracing tools without compromising privacy. With $40,000 of the NSF award, he will focus on finding, testing, and implementing digital technologies that can enable private and secure smartphone contact tracing.

His collaborator, Yaling Yang, professor of electrical and computer engineering at Virginia Tech, is developing the contact-tracing app itself. Their work, and the resulting technologies, will be open-source, enabling researchers and developers around the world to build it into their own solutions. The researchers also have published and presented their findings in conferences and at NSF-organized workshops.

“The idea for this research project was born out of a meeting I had with Patrick when the pandemic just started to unfold around the globe,” Yang said. “We both had a strong urge to contribute our expertise in the fight against this pandemic. We hope that our effort will not only help with the current pandemic, but also will make our society better prepared to combat future infectious diseases.”

Much of Schaumont’s research will focus on the use of encryption and cryptography (methods of scrambling data so only authorized parties can understand it) to protect the information collected by the smartphone app. He’s also investigating best practices and policies that will help shape what kind of data the contract-tracing app will collect, how it will collect it, how it will protect users’ identities, and how and when it will release data to public health officials.

Related Stories

Rhesus monkeys and cats potential spillover reservoirs for COVID-19 virus

Research looks at aerobiomes, trees and implications for public health

Chilblain-like skin lesions reported in adolescents and young adults during the pandemic

“It requires a mix of policy and technology,” Schaumont said. “Some early efforts to create contact-tracing apps did not consider privacy and security to be a big issue. That was a problem. We’re going to change that.”

The researchers will investigate two means of collecting tracking data. With the first, the app would track the location of the user and encrypt any stored information. It would then send the encrypted data, minus any personally identifiable information, to a server used by a public health department.

Using that data, health officials could determine whether the user had crossed paths with anyone who had tested positive for COVID-19 because they also would have that person’s data. Another approach would upload information only from anyone who tests positive for COVID-19.

That information would be made public, without identifying the infected individuals, so anyone would be able to go online and check for themselves if they have been in close contact with someone who has tested positive.

The app will use a range of technologies, including GPS, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth. The combination will help track a user’s exact location, as well as close encounters between contact tracing app users. That way the app would be able to recognize if an infected person was close to someone else when they were contagious.

Having created a prototype contact-tracing app, Yang is testing its ability to trace close contacts and then share that data without releasing the user’s identity.

Schaumont, who is working on this research with four PhD and two master’s students, is preparing to launch a survey about concerns people have with digital contact tracing, as well as their thoughts on the advantages it would provide.